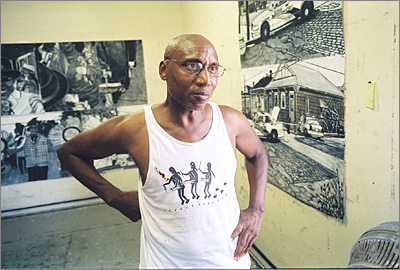

Willie Birch stands in his painting studio in the 7th Ward neighborhood of New Orleans. - photo by Stephen Smith

Internationally renowned visual artist who helped organize The Porch, a community arts center in the 7th Ward.

It's been two years since the catastrophe of hurricane Katrina made life in urban New Orleans even more difficult than usual. In that time, an internationally known painter has deployed art to change the streets around him.

Willie Birch draws scenes close to home; images he sees from the stoop of his studio. There is the thick, tangled vegetation of tropical New Orleans and there are dispiriting yellow ribbons of police tape spreading across yet another crime scene.

Willie Birch's painting studio is in one of the few houses standing on his block in the 7th Ward. Across the street, a young man sells drugs from his home. When the guy got shot some months back, Birch sketched what he saw - not the exchange of dollars for drugs, but the crime scene that followed. Laid out in multiple black and white panels, the charcoal/pastel work depicts a police car at the top of a street cordoned off by yellow plastic tape, officials with pencils pointing down at the ground, hunting for shell casings.

Two youngsters collaborate on a painting at The Porch's summer arts camp. - photo by Stephen Smith

Birch had been trying to get his young neighbor to quit selling drugs. So he was upset when the man got shot. Birch turned to art to do something about it.

"Instead of me sitting around and mourning, I went outside and I just started taking snapshots," he says. Birch used those photographs to begin a new series, called "Shooting." He hopes the paintings will get viewers to question what he calls the madness of New Orleans street violence.

"What's going on there - young black males taking each other's lives?" he asks. His eyes widen behind his glasses, and he continues: "What do we do as a community? Well my role as an artist is to put it down and put it out there where hopefully there is a dialogue."

Hurricane Katrina forced many families in New Orleans to split up - spreading mothers and fathers, aunts and uncles across the nation in search of housing and work. Now there are a lot more young people in the city living without their parents. It's clear to Birch and many others that these youth urgently need guidance and protection. So Birch is doing what he can to put the tool he's always used to make sense of the world - art - into the hands of young people.

A few streets away from Willie Birch's studio, an arts center called "The Porch" is buzzing with youngsters. The Porch is a yellow, single-story building that serves as a summer art camp for kids. Birch and a few fellow artists and musicians organized the center after Katrina to help reach needy kids. Inside, a group of children ages 8 to 14 sit around a table writing rap songs. Their teacher is a hip-hop performer named Voice who makes sure they understand their songs must not glorify drugs, sex or violence.

In another room, children cluster around a table covered with paper and bottles of paint. Their teacher, a sculptor who teaches at Xavier University, encourages them to fill the page with color.

Birch says artists are in a unique position to connect with young people in New Orleans. An artist's role, he says, is to "constantly put things in front of children that say, 'There's another way you can look at your situation. It's all not doom and gloom. There is hope within all of this.'"

Willie Birch is 65 years old. He has a lean body and smooth, round face that make him look 20 years younger. He grew up in the Magnolia housing project in New Orleans. In his early 20s he realized he wanted to be an artist and eventually decamped to New York, where he earned international fame as a visual artist. Nationwide, major galleries and museums exhibit his work.

Michele Levine, who teaches art at Xavier University, works with young children at The Porch. - photo by Stephen Smith

Birch returned to New Orleans in the mid-1990s and began painting the landscape and street scenes of his home town. Now, he says, he doesn't have to leave his neighborhood to get cultural inspiration. "I can go to a Voodoo ceremony in Brooklyn," he explains. But in New Orleans, he says, "It's right in my back yard. A second line will pass in front of my door - - I don't have to go out and look for these things. They come to me."

The flood that came to his stoop when the levees broke in 2005 hasn't much changed the content of his art, Birch says, "except now I'm drawing trailer houses instead of shotgun houses."

Birch has made enough of a connection with neighborhood teens that they respect him. "These kids don't even play in front of my stoop when I'm in there working," Birch says. "Enough of 'em have looked inside my studio to say, 'Whoa, man, this guy's serious. This cat ain't drawing no stick figures in there.'"

To Birch, every day offers a chance to intervene, to step in the path of a kid walking in the wrong direction. In the midst of an interview with radio reporters outside his art studio, Birch takes such an opportunity. He calls over to one of the young teens on the stoop across the street. The boy, Buddy, reluctantly walks over. Birch invites him to join the conversation.

"You wanna be on the radio?" he asks. Nodding toward the microphone, Birch asks Buddy what he is doing to help make the community a better place.

Buddy mumbles, "I clean up in front of my door sometime, and I help people take the trash out." A few more questions from the grown-ups elicit terse responses. Then Buddy escapes back to his house.

Birch seems encouraged. "See?" he says, "That's beautiful. It's little small things like that, you know? Hopefully that makes a difference in his life," he says.

Birch believes that by holding Buddy up as a local hero to important-seeming visitors he can expand Buddy's view of what he himself might achieve one day.

Hip hop artist Voice coaches camper Nykira during the girl's first rap recording at The Porch's summer arts camp. - photo by Stephen Smith

Birch is trying to plant seeds of possibility in the young people around him. In one case, this meant making art for kids to "steal." Instead of arranging a conventional art show during Mardi Gras season, Birch and some other artists made up 300 posters featuring 10 different African American legends from New Orleans. They included the pianist Jelly Roll Morton and revered restauranteur, Leah Chase.

Birch's group stapled the posters all over his neighborhood, careful to put them at a kid's eye level. The posters went up on a Friday morning and by Monday were all gone. "What does that tell Willie?" Birch asks. "Instead of putting up rap stars in your house, now you got these people," he says. "We'll do it next year. People will be looking for it, like an Easter egg hunt."

"That's a successful project," Birch adds. "And we know it's still working its way through the child. Now he has a piece of art in his house instead of a piece of newspaper on his wall."

Birch was deeply relieved when the young man dealing drugs across the street survived the shooting. But as Birch stood on the sidewalk speaking to visitors the man was approached by an apparent customer. Birch watched them. They disappeared around the back of the house. Though the young drug dealer seems to be back in business, Birch holds out hope for him. "That's where culture becomes so important," Birch says. When a second-line parade comes marching down the street, it's showing that another way of life is possible, a life of creation not casualties.

And, Birch observes, "They can't sell drugs on the corner when a second line's going through."

Likewise, when these young people see Willie Birch prospering as a painter, it gives them a valuable image: an African American man from inner-city New Orleans who is succeeding on his own terms. It shows them, Birch explains, "that you don't have to sell drugs. You don't have to be a gang-banger. You don't have to break into people's houses. This is a legitimate way of making money. But it's also a legitimate way of speaking to the ills of society."

Willie Birch looks at the young men across the street and finishes his thought, "If you've saved one, you've saved a thousand."

More from Routes to Recovery

|