| ||||

| ||||

|

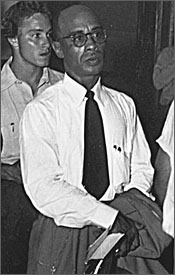

Heman Sweatt applied to the University of Texas and the school denied him admission because he was black. With help from the NAACP, Sweatt immediately filed suit. A Texas court ruled that the law school would have to integrate because it did not offer a law school for blacks. But the court also gave the law school an out: Texas could block Sweatt from going to the white school if the state could build a separate law school for blacks in six months time. Thurgood Marshall directed strategy in the Sweatt case and coached the plaintiff to tell an appeals court judge he would refuse to attend a law school for blacks, however new, because segregated schools were inherently unequal. The judge ruled against Sweatt. After Marshall's team lost a second appeal, the Sweatt case headed to the Supreme Court. As the Sweatt case made its way through the courts, some prominent black pundits criticized the LDF for attacking the principle of separate-but-equal. They argued the strategy was undermining all-black schools and threatening the meager state funding those schools received. In a speech to the Texas NAACP in 1947, Marshall responded: We are convinced that it is impossible to have equality in a segregated system, no matter how elaborate we build the Jim Crow citadel and no matter whether we label it the 'Black University of Texas,' 'The Negro University of Texas,' 'Prairie View Institute,' or a more fitting title, 'An Apology to Negroes for Denying them Their Constitutional Rights to Attend the University of Texas.' Despite his public stance, and personal conviction, Thurgood Marshall was still reluctant to make a direct challenge to the principle of separate-but-equal in the public schools. If the Court upheld Plessy, he reasoned, it would be all the more difficult to get the Court to reverse itself in the future. To build his case against segregated schooling, Marshall enlisted top legal scholars, including Yale professor Thomas Emerson. Emerson and colleagues at Yale wrote an amicus brief arguing that Jim Crow schools were inherently unequal and, in fact, illegal. Submitted under the name The Committee of Law Teachers Against Segregation in Legal Education, the brief was signed by 187 law professors from top schools across the country. The document said that segregated schooling violated the 14th Amendment and that, "in countless ways, separate legal education cannot be equal education." On June 5, 1950, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously in favor of Sweatt. The Court ruled that a makeshift "colored" law school was inherently unequal to the University of Texas. "A law school," the Court decreed, "[is] the proving ground for legal learning and practice, [and it] cannot be effective in isolation…Anyone who has practiced law, would not choose to study in an academic vacuum, removed from the play of ideas and the exchange of view with which the law is concerned." Thurgood Marshall and his team had reached a crossroads: the Sweatt ruling, along with two other favorable rulings issued the same day, brought a straight challenge to Plessy within the LDF's reach. Marshall knew he could file a slew of lawsuits across the South showing that black public schools were patently inferior to white ones, thus forcing equalization of racially separate schools. Or, Marshall and his colleagues could finally attack the principle of separate-but-equal head-on. In 1950, Thurgood Marshall decided it was finally time to launch a direct attack on Plessy. |