A Divided Community

This year there were two ceremonies for Ahmici on April 16, the anniversary of the massacre.

At the area's main mosque, thousands of Muslims gathered for early morning prayers for the massacre victims. They then climbed up a grassy knoll to the cemetery where the victims were buried nine years ago by British peacekeepers. There the crowd listened to a man reading the names of Ahmici's dead.

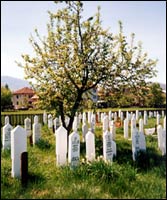

Many of Amici's victims were buried by British UN troops in a cemetery behind the main Mosque in the nearby town of Vitez. Photo: M. Montgomery / American RadioWorks

|

On the same day and just across the main road from Ahmici, local Croats staged their own commemoration at the foot of a huge neon cross. They prayed not for the Muslims killed at Ahmici, but for Croats killed in the civil war. It was a provocative act and meant to be.

The ceremonies showed that bitter divisions between Muslims and Croats persist in and around Ahmici. Neither side talks about hopes for reconciliation in this generation. This is the exact opposite outcome to that intended by the war crimes tribunal. Its central mission is to focus blame on individuals most responsible, not along ethnic or national lines. And yet for many villagers, the trials were a failure.

Sakib Ahmic says the jailing of commanders gave little comfort. He wanted the actual killers sent to jail. The outcome of the trials hardened Sakib's hatred of Croats.

"In my opinion they're all guilty because not one Croat helped protect Muslims here," says Ahmic. "Had they helped save even one Muslim life I would say, okay, here is some humanity."

Sakib's daughter Suhreta, whose husband was killed in the massacre, is outraged that the tribunal released the Kupreskic brothers without telling survivors why.

"No one from The Hague and no one from government came here," she says. "It's as if dogs were killed and not people. I'm speechless as to why no one came had the sense to come and explain why they were released. How is it that war criminals can be released."

A third Muslim from Ahmici, a café owner named Mehmet, says the tribunal failed everyone, Muslims and Croats.

"Four years after our return here, we still don't know the truth," says Mehmet. "My relative thinks his neighbor killed his father. This neighbor, knowing that he is suspected, is afraid and doesn't sleep at night. That's what we have here. It's not justice, but a balance of fear."

Zoran and Mirjan Kupreskic, the former defendants, are unemployed and living off charity with their families in rented apartments two miles from Ahmici. They have publicly discouraged Croats from seeking revenge on Muslims. But the brothers want another kind of retribution. They're suing the tribunal for wrongful imprisonment. Zoran says The Hague tribunal produced nothing but injustice for Croats.

"The problem is that because the court prosecuted innocent people like us and others, it has completely lost the confidence of Croats," says Kupreskic. "Everyone knows we were prosecuted as Croats, not criminals. In the end, they chose the people they could get. Not those who were guilty."

There are no obvious signs of hostility in Ahmici as Croats and Muslims continue to rebuild. But there's little effort at reconciliation, either.

Eric Stover of U.C. Berkeley says Ahmici is not an isolated case in the Balkans.

"It's clear from our studies throughout the former Yugoslavia that war crimes trials, at least in the short run, tend to further divide communities," he says. "The fact that there are so many people who planned and carried out the war crimes in the former Yugoslavia means that in towns today there are still war criminals walking around and everyone knows who they are…and so you set up a dynamic where there won't be any reconciliation until there are further trials that deal with the smaller fish."

Graham Blewitt, the ICTY deputy prosecutor, says the tribunal probably erred by indicting so many lower level suspects. But Blewitt says the Kupreskic case was undermined by efforts to intimidate Muslim witnesses. "The drop out rate of witnesses was significant," he says.

Blewitt says he is surprised to hear that the prosecutors never explained the Kupreskic verdict to Muslim witnesses living in Ahmici.

"It's important that these people understand the process. That's why the tribunal puts so much effort in its outreach program. If we don't explain a result like the Kupreskic case, then we're failing in our duty toward these victims."

Albert Moskowitz, who prosecuted the Kupreskic brothers, says it would be impossible for any court to heal all the wounds of war. But he says The Hague tribunal was successful in Ahmici, because it jailed the leaders.

"Any reasonable person looking from afar would say that this is a good measure of justice for as to what happened in those villages, including Ahmici," says Moskowitz. "But if you're a villager in Ahmici trying to rebuild your life and all you know is that your husband and your brother and your mother have been murdered by people who are still walking around claiming that this was a defensive operation—that's cold comfort."

There will be no more Ahmici-style prosecutions at the UN Tribunal. Instead, future prosecutions will almost always focus solely on high-level officials. The tribunal says it must concentrate on getting the leaders of the wars in former Yugoslavia if it is to complete work on schedule within seven years. Tribunal officials would like to hand off cases against lower level war criminals to Bosnia's supreme court. But they say it may take years before that court reaches international standards for fairness and independence.

Gary Bass, an expert in international justice at Princeton University, says the kind of justice offered in The Hague will be largely symbolic, punishing the few for the crimes of the many.

"In domestic society we think that any person who commits a crime deserves to be punished. And when you're dealing with war crimes you're never going to be able to have that kind of perfect accountability. So you're left with this sort of symbolic nature. I don't think we should kid ourselves that you can say oh look we've set up a war crimes tribunal in The Hague. We've dealt with it, we've solved it."

Next: Part III Rwanda's Revolutionary Justice