Waiting for Gautreaux

Dorothy Gautreaux, a community activist who helped file a racial discrimination suit against the Chicago Housing Administration.

Photo courtesy BPI/"Waiting for Gautreaux"

The most convincing story about the geography of opportunity came from the so-called Gautreaux program. Polikoff had filed a lawsuit alleging racial discrimination by the CHA on behalf of Dorothy Gautreaux, a community activist who lived in public housing on Chicago's south side. Like many lawsuits alleging discrimination, it's a complicated story with plenty of legal twists, setbacks and heroic moments. But in the end, Dorothy Gautreaux won her suit through a series of rulings that went all the way to the Supreme Court in 1976, where Polikoff bested his former classmate and rival in the case, Robert Bork. Dorothy Gautreaux died before that ruling, but the settlement is still known by her last name.

To comply with the Supreme Court, HUD tapped its relatively new housing voucher program to move public-housing residents into private housing in the city and suburbs. HUD turned to the Leadership Council for Metropolitan Open Communities, a nonprofit run by a dedicated group that had long battled to desegregate housing in Chicago and its surrounding environment, to run the program. From 1976 through 1998, some 7600 families moved out of the projects, with one-half moving to better neighborhoods in the city and the other half moving to the suburbs.

By design, public housing residents had to live in suburbs that were 70 percent white, although in reality they were 90 percent white. Suburban communities were much safer than the gang-ridden projects. The jobs were in the suburbs. And suburban schools were better than comparable city schools.

"It was seen as an opportunity program," says Paul Fischer, an urban scholar and professor emeritus at Lake Forest College. "The hope was that going to better schools in safer neighborhoods with greater job opportunities would be better able to move people out of poverty."

It wasn't easy on the families, however. Many encountered racism. For example, Valencia Morris moved her three daughters from Chicago's troubled Altgeld Gardens project to Woodbridge, an all-white suburb 20 miles west of the city. Her daughter Jamillah was 5.

"It was the teachers. It was difficult to walk down hall because the teachers would move their line of students away," recalls Jamillah. "Any time we entered a circle or group we went in knowing we had to give people time to get used to us."

Still, once free of the projects, Valencia Morris went back to school and became a nurse. Her three daughters all got college degrees and went on to professional careers.

Morris and her children might be exceptional, but they weren't the exception. Children who moved to the suburbs were more likely than their counterparts who remained in more segregated neighborhoods in Chicago to graduate from high school, attend college, and go to a better college. Those that didn't go on to higher education ended up with jobs that offered higher pay and benefits.

"The program changed so many lives of very average people," says James Rosenbaum of Northwestern University.

Adds Paul Fischer: "If you look at if from a multi-generational perspective, the program did provide opportunities for families. It did provide opportunities for upward mobility as you move from one generation to the other."

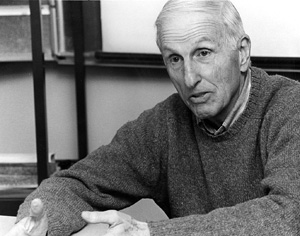

Alexander Polikoff, the attorney who took the Gautreaux suit to the Supreme Court, says strong social services are essential in housing voucher programs.

Photo by Jason Reblando

The lessons scholars drew from the Gautreaux program prompted HUD to fund a much bigger five-year, multi-city experiment called "Moving to Opportunity" or MTO in 1994. (Chicago is one of the five cities.) There are many other residential mobility initiatives, most notably as part of HUD's Hope VI initiative. Whatever the label, reformers inspired by Gautreaux were disappointed as the residential mobility programs got bigger. So far, the experiment has fallen far short of Gautreaux. A number of factors conspired against the break-up of public housing turning into the geography of opportunity. Parents are not getting better jobs or incomes, and young children aren't showing gains in schooling.

What happened? Polikoff, a veteran of many legal fights over housing, emphasizes the lack of good, sustained social service support for the families that take vouchers. The Gautreaux program had worked hard with those that moved out of the projects, preparing them for life in their new, and very different, community.

"We are dealing particularly with the families who are moving out of the high-rises and have all sorts of tremendous problems: health problems, mental and physical, domestic violence, educational deficits, skill deficits, credit problems," he says. "To enable families of this sort to succeed they've got to have help once they're there."

In their current haste to move residents out of the projects, housing authorities allowed tenants to move into nearby low-income and mostly African-American neighborhoods. Problem is, the children ended up going to the same or similar schools and the job market was the same for the parents.

"Why do we expect people's job opportunities to change if you don't change labor markets?" says Rosenbaum. "In Gautreaux over 80 percent of children were going to schools above average achievement, above national average. In Moving to Opportunity almost all schools are below the national average. Why would we expect achievement to go up?"

Why indeed.

Continue to From Development to Neighborhoods