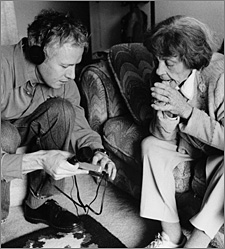

| John Biewen with Kitty Shenay

photo by Tom Rankin | |

Reporter's Notebook - Hospice

By John Biewen

People ask me, "What are you working on?"

A story on the hospice movement, a historical look, I say. And I'm following a terminally ill patient.

"That must be depressing."

More than a few friends and acquaintances reacted with some variation on this theme. It might seem like a natural reaction, but it jarred me a little every time. It didn't square with the experience I was having.

Sure, on one level the very subject of death is depressing. It's the Big Bummer, the central problem of the human condition. But we already know that. Routine denial notwithstanding, we know death's coming and we've had our whole lives to get used to the idea. I couldn't see why it should be depressing to document a dying person or to explore a movement whose mission is to care for people in their last days.

Maybe my friends were thinking not of death itself but of the messy business of dying - that it would be painful to watch a person suffer through the decline of late-stage cancer. "It's not that I'm afraid to die," as Woody Allen famously put it, "I just don't want to be there when it happens." (I'd seen dying people and dead bodies before, but I'd never been present repeatedly during the process as I would be with Kitty Shenay.)

The first time I walked into Kitty Shenay's apartment and shook her hand, I was shaken. I'd faced awkward moments before in my work, approaching people and asking to document them because they were in some painful circumstance, such as poverty or prison. This, though, took that awkwardness to a new level. Kitty was frail and jaundiced. She'd been given six months to live four months ago. This woman was dying. Reporters are often called jackals. At this moment the metaphor seemed too apt.

But Kitty's strength and openness put me at ease. She had agreed readily to participate in the documentary. Kitty welcomed the chance to let more people know about hospice, she said. Several times I brought a colleague, Will Atwater, or he visited Kitty by himself to help in the recording. I asked if I could bring photographer Tom Rankin along, and she said yes without hesitation. I asked her to record an audio diary if she felt up to it, and she did so until just a couple of weeks before she died.

What really transformed the experience, though, was Kitty's personal warmth. She seemed to take a shine to me, and the feeling was mutual. The third time I saw her, at the family's reunion in Fayetteville, I was sitting at a small table in her granddaughter's kitchen, talking with Kitty's relatives. She came in, sat down beside me and thanked me for coming. Then she took my hand in hers and didn't let go. There we sat, she holding my hand as we chatted as though I were a favorite nephew. We talked college basketball and the pleasures of summer in Minnesota, where she'd vacationed several times. She made sure that I got a piece of her marvelous pound cake.

I saw Kitty Shenay about once a week for the last two months of her life. The experience was poignant. Towards the end it was disturbing, even shocking. One day she was frail but fully present and sharp-witted, days later she'd become a near corpse, unconscious and struggling for her last breaths. And, indeed, a few hours after that I looked upon her actual corpse.

It was emotional. I wiped away tears several times in Kitty's presence, and many more times while listening back to her tender moments with her daughters and with her nurse, Roland Siverson.

But depressing? No. In fact, I found the experience curiously uplifting.

Hospice workers and volunteers will know what I'm talking about. Their work is not for everyone. Some people get too attached to their patients, get worn down by the relentless losses and need to find another job. But many hospice nurses, doctors, social workers, chaplains and volunteers talk about their work with dying people as a privilege.

"I'm surprised that there aren't more nurses that are just chomping at the bit to get into hospice," Roland Siverson told me. "Because it's so interesting and it's so fulfilling, and we have the opportunity to work with people, not just feed them their meds and get on down the road, but to actually spend some time and develop that relationship with patients. Those of us who are in it, we love it."

I feel that way about my work documenting the lives of "ordinary" people, often as they face hard challenges. I'm moved by the quiet heroism people show. I'm unendingly grateful to those who share their stories, who allow me to hang around with my tape recorder. Doing such work is an enormous privilege, one I've never felt more acutely than I did with Kitty Shenay.

We're all going to die. The question is, until then, how will we live? Kitty spent her last months doing the things she loved with the people she loved. She endured pain and discomfort as her body broke down, but nothing overwhelming, thanks to modern pain medications. And in her last days, the people surrounding her, her family and her hospice caregivers, were determined to treat her with dignity, tender care, and love. And that's exactly what they did.

To observe this was not depressing. It was beautiful.

Back to - The Hospice Experiment

|