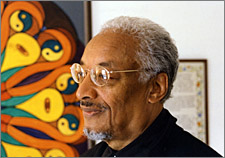

| Mwalimu Imara

photo by John Biewen | |

A Revolution in Dying

part 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Kübler-Ross in Chicago

Imara met Kübler-Ross in 1966. By then she'd married an American and taken a job as a psychiatrist at the University of Chicago. Imara was a divinity student and a chaplain at Chicago's Billings Hospital. He got assigned to work with Kübler-Ross on a controversial seminar in which she interviewed dying patients before a classroom of medical and divinity students.

"The seminars were very popular," Kübler-Ross says. But "the university hated me. Oh, they had so many hang-ups."

"What they were concerned about," says Imara, "was that if the patients heard the word death or talked about death it somehow would destroy their peace of mind."

In fact, Imara says, patients were far less afraid of the subject than their doctors were. "We never told the patients they were dying. We asked them, 'How sick are you, what are your concerns right now?'" Invariably, he says, the patients soon volunteered matter-of-factly that they expected to die soon.

Still, Imara recalls one furious doctor who confronted Kübler-Ross in the crowded lobby of the hospital. "[He] started screaming at her, saying things like, 'What kind of a ghoul are you?'"

At one point, Imara says, the enraged doctor took a menacing step toward Kübler-Ross. "And I took a step towards him," says Imara. "I'm six foot, and I was in a heck of lot better shape then than I am now. I remember feeling [Elisabeth] grab my coat on the side and give it a firm yank. ... I knew she was there, she was not in the least bit threatened by this guy."

Though controversial within her own hospital, those interviews with dying patients were the basis for Kübler-Ross's book, On Death and Dying. Its publication made a sensation in 1969. Nonetheless, the University of Chicago said Kübler-Ross's work wasn't real medical research.

"I said, five thousand pages are not enough, huh? That's not enough research? 'No, it's not science.' I said, tough shit, that's your problem not mine."

Chicago declined to offer Kübler-Ross tenure. She and the university parted ways.

By that time, though, Kübler-Ross's writing had made her a celebrity. She went on the road, lecturing and leading seminars on death and dying. And, by the mid-1970s, advising groups of nurses and others who wanted to create hospice programs. "Essentially what she did was to have an independent university of her own," says Florence Wald.

When people heard or read Kübler-Ross and wanted to take action, they had a model. In 1967, Cicely Saunders had opened the world's first modern hospice in a leafy part of south London. She named it after the patron saint of travelers.

Next - St. Christopher's

|