|

| |||||||||

The Army Townpart 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 People in Fayetteville know that lots of outsiders, especially in more upscale cities, see their town as undesirable and blame the military. But some people in town say the big military presence has had positive social effects, too. Take race, and the example set by Fort Bragg. "The Army - black and white integrated back in the '50s. Fort Bragg was one of the first places that took place, too, the paratroopers," says former newspaper editor Roy Parker. He points out the military ended racial segregation well before most of Southern society did. In 1951, Fort Bragg ran its own segregated schools for the children of soldiers. The white kids in a spacious building, the black children squeezed into a smaller one. "The sweet lady who was the principal of the white school, she said 'This don't work. Those black kids are sitting over there in that little thing and I've got all this room over here,'" says Parker, "so she integrated them. Classroom by classroom. She caught hell for it, but we love to say that old Mildred Poole integrated the Fort Bragg schools before the Supreme Court or anybody else said do it." That is, three years before the Brown vs. Board of Education decision, and more than a decade before segregation ended in the Fayetteville public schools.

"Black and white got along on post. But off post, that was a different story, man," says Phillip Allen, a 54-year-old Vietnam veteran. His father, James Allen, was a mess sergeant at Fort Bragg after World War II, so Phillip grew up there in the 1950s and '60s. "We used to go to the movies every Saturday, us kids. … Who was the one that had the spaceship? … Flash Gordon." The father and son remember going to movie theaters during the Jim Crow years in Fayetteville. "And the blacks had to be in a balcony upstairs," says James. "We couldn't go in the front door," says Phillip. "We had to go in the side door!" "The side door. … And they went upstairs."

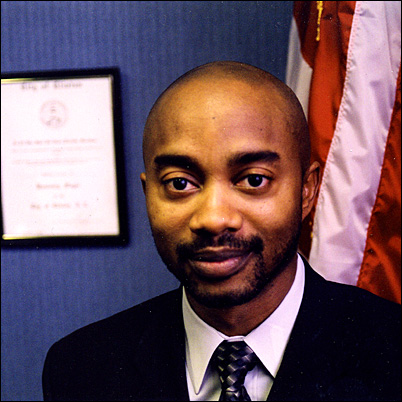

"And the whites were downstairs." And by contrast, on Fort Bragg. "I think the main movie house was on main post, wasn't it, Sarge?" asks Phillip. "Across from Hedrick Stadium. We blacks and whites always went to that same movie and we all got along. We'd whoop, hollered and everything else, you know what I mean?" When black students from Fayetteville State sat in at segregated lunch counters in the early '60s, small groups of soldiers, black and white, went downtown to support them. Nobody claims Fayetteville has solved racial inequality, but many argue it's more open and tolerant today than it would have been without the military. The town elected its first black mayor, Marshall Pitts, in 2001. "When I was elected mayor," says Pitts, "it was another sign to folks across the state who have previously seen us in a negative light, said, 'Well, you know, maybe things are happening down there. They're becoming more progressive as a community.'"

Continue to part 6

| |||||||||