| |

Eddie driving the van that a charitable group bought for him. Photo: Steve Schapiro / American RadioWorks |

Eddie climbs into his 1991 Dodge van and heads to a poor part of north Durham. He moved to North Carolina after his release because of a spiritual group he'd heard about in prison, the Human Kindness Foundation, which is based near Durham. The group helped Eddie find an apartment here, though he still has to pay the $575-a-month rent. A wealthy volunteer with the foundation bought Eddie his van for $1,700.

"I'm glad to have it; it certainly beats walking," Eddie says as he drives up Roxboro Road. "I don't know what I'd do without it because I certainly wouldn't be able to do painting jobs. But it needs a little work. The brakes in the front need to be redone. It blows smoke now, and it seems that that situation's getting worse and worse. I can't afford the repairs right now."

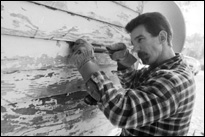

When Eddie got to Durham he joined a local Church of Christ, and his connections there get him some of the informal work he drums up. This day he's working for a friend from church who owns a home in need of repair. Behind a big old house with worn and warped clapboards, Eddie spreads a drop cloth on the ground and sets to work scraping away old paint. The job will pay him ten dollars an hour.

| |

Eddie at work Photo: Steve Schapiro / American RadioWorks |

"I'll just work out here for maybe two hours or so and just make a little bit of money today," Eddie says.

Like Eddie, many ex-convicts struggle along on sporadic, informal work. Researchers have found that a prison term takes a slice out a person's earning power - a 15-percent slice, on average. Since most people who go to prison have few marketable skills to start with, a 15-percent wage hit often means poverty. Federal and state laws ban many felons from holding jobs in schools, nursing homes or airport security. Eddie's home state of New Jersey has a long list of jobs off-limits to certain felons - from bartending to firefighting, to working at a racetrack or as a parking attendant. Before his arrest, Eddie held jobs as a postal worker and an optician and he managed a Radio Shack store. Since prison, he says, he's applied for dozens of entry-level jobs.

"I went into Wal-Mart recently," Eddie recalls, "and I filled out an extensive application and I sat there for quite some time waiting for someone to come and take my application. And a fellow came out of the office, and he was standing right next to me, out in the open, and he said, 'The manager wants to talk to you so could you please just wait for a few more minutes. He wants to sit down with you and discuss things.' I said, 'OK, fine.' He came back out a few seconds later and he said, 'I noticed that you forgot a few blocks on this application. Could you just fill them in?'"

Those empty blocks were the questions about the applicant's criminal record, Eddie says. He says he won't lie as a matter of principle, but he sometimes leaves the questions blank hoping he'll get a chance to tell his story in person. So now he filled them in.

"And where it said, 'Have you ever been convicted of a violent crime?' I checked no because I haven't. And then it said, 'Have you ever been convicted of a felony?' and I checked yes because I have. So he said, 'All right, thank you,' and he went back in that office. And then he came out another door. This time the counter was between he and I, the fella that I had just shook hands with and been talking to, and he said, 'Is this the number that you can be reached at?' I said, 'Yes, it is.' He said, 'Well, the manager's in a meeting right now.' And I said, 'Look buddy, you don't need to lie to me. I see what's going on. And I'm just gonna pray for you.' You know. And so I left," Eddie says.

Eddie says he understands why a manager might push a convicted felon to the bottom of the applicants' pile, but he claims to have done things differently himself. "When I was a manager for Radio Shack and guys came to me and were honest with me and said, 'Well, I'm on probation' or 'I got to go to AA' - I hired them."

| |

Gudrun Parmer directs a Durham County program that provides job training and chemical-dependency classes to a small number of returning ex-inmates. Photo: Steve Schapiro / American RadioWorks |

If Eddie really behaved that way as a manager, he apparently wasn't typical. Gudrun Parmer directs a Durham County program for ex-prisoners. She says ex-cons had a better chance of finding work a few years ago, when jobs were plentiful.

"A lot of times the employers were willing to give them a break on the criminal record because the need for workers was so great, especially in construction, landscaping, the service industry. But now they can pick. Now they have more people looking for work than there are positions. Our guys are usually the last ones on the list," Parmer says.

Some advocacy groups suggest policies to make ex-prisoners more attractive to employers - such as expunging the criminal records of ex-cons who stay out of trouble for a given period, or giving tax credits and other incentives to employers who hire former inmates. In the meantime, 're-entry' has become a buzzword. Lots of crime experts and corrections officials say there ought to be more programs to help ex-convicts succeed - job-training courses, halfway houses and drug treatment programs. The actual growth of such programs is slow, partly because governments are strapped for money. That leaves religious groups to fill the void.

Next: Faith-based Support