|

| Story | Photography | Read Others' Stories | |

|

page 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8

Failures at the Border The front lines of the War on Drugs are right next door. Mexico now supplies 60 percent of the cocaine to the American market. Ironically, it was a U.S. law enforcement success that pushed Mexico into the major leagues of drug smuggling. In the 1980s, when an all-out effort moved Colombian traffickers out of South Florida, they set up routes in Mexico and looked for Mexican partners. In the 1990s when the Medellin and Cali cartels were smashed in Colombia, Mexicans took majority control of the trade. The battlegrounds are now the towns along the Mexico-U.S. border. It is a losing battle, as the constant demand in the United States spurs new generations of smugglers to supply more cocaine, heroin, and marijuana at the lowest prices in years. The San Ysidro port of entry, south of San Diego, is the country's busiest border. Across 16 lanes of traffic, thousands of cars line up every day to go from Mexico to the United States.

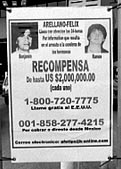

U.S. custom officials have only 30 seconds to question each driver. Is this a drug smuggler? Some surely are. But how to pick them out in the 43,000 cars that cross every day? Or among the 25,000 pedestrians who pass through these turnstiles at the border? To take any longer to check them out would slow the rapid growth of trade, and that is the priority both in Mexico and in the United States. "There are many of the things that are more important than the drug policy in Mexico," says Ed Heath, who was the Drug Enforcement Administration's Mexico chief thru the 1980s. "We do want to do something about it, there is no question about that, however the commitment has to be there. Just a couple of miles away, Tijuana, Mexico, offers cheap and plentiful labor and proximity to U.S. markets. The qualities that make Tijuana important in the global economy make it a haven for drug smugglers. "The borders there, it runs the entire width of the state, and they sit on the other side," says Vince de la Montaige. "I can just visualize them sitting on the other side laughing at me all the time." De la Montaige retired from the San Diego FBI office in May of 2000. He was part of a U.S. task force formed to capture and arrest the Arellano Felix organization. The Arrellano Felix family, led by Benjamin and Ramon, moved to Tijuana in the 1980s. They have been in business longer than any other cartel in Mexico. "They are a tight family. They've broken it down where they have people in charge of the transportation, people in charge of the financing—but the violence was Ramon, basically. And he has a cast of assassins that will do anything for them."

The Arrellanos have been linked to the murder of two chiefs of police in Tijuana. They've also been accused of torturing and killing a federal investigator and killing prosecutors, judges, and journalists—violence that takes place within a half-hour drive from downtown San Diego. In Tijuana, the Avenue de Revolution is a noisy street of tourist bars and tourist pharmacies. Americans flock here to get the things that the U.S. government says they can't have. It's a playground for young tourists, but a violent playing field for drug dealers. In the past 15 years, the Arrellano Felix organization made drug trafficking a sophisticated business, using cell phones and high-tech electronic equipment to keep tabs on other traffickers or anyone suspected of informing for the U.S. or Mexican governments. But the Arrellanos revolutionized the business in one other important way. They recruited some of the sons and daughters of Tijuana's top families to run their drugs and do their killing. Known as the "narco juniors," many of them are American citizens. One former narco junior agreed to an interview if we protect his identity. We will call him "Steve." He says the attraction was simple: There was glamour, and there was greed. "I just got out of law school, and you just got your practice going and you're working hard, and still, you know, the girl you'd like to date is going with … a frigging drug dealer … just because he can buy her Dom Perigon all night, and that's what you see in the discos. You see all these drug dealers buying girls all this stuff, and you can't afford that. So the only way you can do that is by getting in the action. [There was some risk] but when you're a young kid you don't think that way. You're bulletproof." Back in San Diego, the narco juniors were coming to the attention of U.S. law enforcement. In the mid 1990s, Gonzalo Curiel, an assistant U.S. attorney handled some of the cases. "It makes you scratch your head, and go, 'How are these people wired? What was the lure? What was the draw?' " says Curiel. "The best I could tell, the lure was the raw power that was associated with an organization that was feared throughout Mexico." Steve, the narco junior, began laundering money, and moved up to moving cocaine. "Now you're risking loads," Steve says. "Now, you're using your house as a stash house. The big thing is: Don't violate the law in the United States. Be real careful in the U.S. In Mexico, somebody will get bought off, someone will fix this." next: Supply and Demand > | ||||||||||||||||||||||||