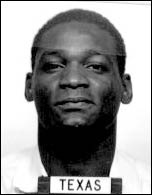

Death Row - Bobby Moore

The nation's busiest death row, the 2900=inmate Allan B. Polunsky Unit, is in Livingston, Texas, an hour north of Houston. The sprawling, gray two-story complex sits behind multiple razor wire fences overlooking a broad, open plain of buttercups. Visitors are led through an electronically operated door along an immaculately tended, flowered path.

CASE IN QUESTION: Bobby Moore

Photo: Texas Department of Corrections |

A second security checkpoint guards a long room where shackled death row inmates— their shirt backs marked "DR" in ten-inch black letters— are led into phone-booth-size steel cages with thick plexi-glass windows.

"My name is Bobby Moore. Having been on death row for 22 years now, I have witnessed many men being carried away to the execution chamber. Many here do not want the time to be up— and some do."

Bobby Moore, now 42, was sentenced to die 22 years ago for the shooting death of James McCarble in the course of a bungled robbery at a Houston supermarket. Like other men and women who have spent years on death row, Moore insists the experience has affected him profoundly.

"Any person that believes in God, I think, would agree that people do change," says Moore. "And I'm no longer the person I was 20-some years ago. I have changed. I regret what I did in the past and I learn from my mistakes every day of my life here."

Similar claims of change and redemption have invariably been dismissed by the Texas parole board and governors, among them George W. Bush, who signed off on 152 executions.

Fred Baca was so disturbed by his trial experience that he went to the judge and asked to meet the man he'd just condemned to death. Photo: Lynn Stewart

| |

Moore is only alive today because a federal court ruled he would probably not have been sentenced to death except for the "gross incompetence" of his trial attorneys. That 1995 ruling led to a "re-sentencing trial," a trial in which jurors were told Moore was guilty and that they were only to determine his sentence. This new jury also voted for death. Fred Baca, the jury's foreman, describes what he calls a "horrific" crime.

"Two people went in and were holding people, were taking money, with Bobby seemingly a lookout guy with a shotgun," explains Baca. "A woman screams, things get out of hand, Bobby goes over to the cashier, the shotgun goes off. It literally blew this man's head off."

Baca was never comfortable with Moore's death sentence. A self-described conservative Republican businessman, he says jurors didn't understand some of the language in their instructions— the term "culpability," for example, and the meaning of the phrase "continuing threat to society." They also asked the judge to tell them which evidence could be considered "mitigating," that is, which evidence lessened Moore's responsibility for the crime. But Baca says questions to the judge went unanswered so often that they finally stopped asking.

"We were drowning, and we wanted some kind of help. And when it's that serious, for God's sakes, when you're pleading for help, you have to give us something. We were reasonable people, intelligent people, making a very difficult decision, asking for help."

| | LEGAL TERMS DEFINED

Culpable

Deserving blame as wrong or harmful.

Mitigating Factors / Circumstances

Information about a defendant or the circumstances of a crime that might tend to lessen the sentence or the crime with which the person is charged. This information does not negate an offence or wrongful action, but tends to show that the defendant may have had some grounds for acting the way he/she did. For example, when a starving man steals bread to satisfy his hunger, this circumstance is taken into consideration in mitigation of his sentence.

|

What most confused the jurors was whether Moore could be paroled if given a life sentence. But Baca says Texas law prohibited jurors from discussing parole.

The jurors concluded they had only two choices.

"The options came down to death or, in our minds, release to the general public," says Baca.

Would Moore ever be paroled? Extremely unlikely. To get out, he would need the approval not only of the state's highly political Board of Pardons and Paroles, which has never granted parole at the request of a death row inmate— but the governor as well. In the end, Moore's jury did what many juries do; they ignored the judge's instructions. Believing that Moore might be paroled in 15-20 years, they voted to execute him.

Fred Baca was so disturbed by his trial experience that he went to the judge and asked to meet the man he'd just condemned to death. Today Baca is one of Moore's most outspoken advocates.

"An injustice is about to occur," says Baca. "The truth is, executing Bobby Moore today is as senseless as the killing of the store clerk in 1981. It doesn't make any sense."

Baca says Texas needs a clear 'life without parole' statute, so jurors will know that dangerous men they don't want to execute will never be released. And he says, citizens who are asked to hand down death sentences have a right to an explanation of things they don't understand.

Next: Judges Don't Want to Retry Cases