|

||

|

|

|

|

Korean Adoptees Remember |

||

|

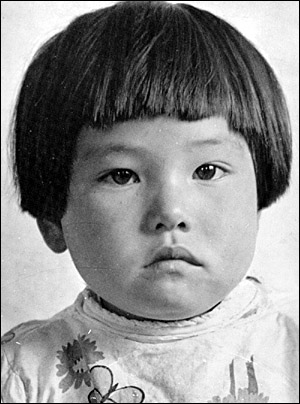

What Happens to the Cute Babies When They Grow Up?

"I was almost 4 when adopted," Cox says. "I feel particularly grateful to have as a part of my story having known Mr. Holt briefly as a child." Cox explains that she was living in the orphanage in Inchon and it was getting overcrowded. The director called Harry Holt, who came and selected five children to bring to America for adoption. "And one of the little children was me," says Cox. "He told my parents I had a very sad face and he couldn't sleep without taking me home." Cox says she remembers Holt comforting her when she awoke from a bad dream. "He was my grandfather before I had a family," she says. Cox now serves as vice president of Holt International. The agency founded by Holt is still one of the largest private agencies in overseas adoptions. In the 1960s after Holt died, Cox says the agency did hire professionally trained social workers But in those early, frantic days in the 1950s, there is no question in Cox's mind that Holt saved children desperately in need of families. "There were all of these children who had been born to Korean mothers and UN soldier fathers," says Cox. "They were mixed-race they were certainly not going to blend in society. The country still prefers a purity of lineage, that was hugely a problem." The children faced certain discrimination in Korea. But Cox says what would happen to them in America was unknown. "The idea that we were transplanting children from one country to another, children of a different race and ethnicity - those were huge issues," says Cox. And there were many skeptics, particularly in the child welfare community. Cox says they said, "They're cute babies, but what would happen when they grow up?" Cox says no one really knew what would happen. Now, graduate researcher Kim Park Gregg is trying to find out. She's collecting oral histories from adult adoptees around the country. She records Jenifer Jacobus, in Vancouver, Washington, who tells her, "The great thing about growing up in my family was how accepted I was." But a little later in the interview, Jacobus laments that the acceptance she felt in her family didn't extend to her peers. "Kids always called me like names, racist names and things that I didn't understand," she says. As a child, Jacobus didn't tell her parents about what was happening to her. "I just kind of accepted that that was just my lot," she tells Park Gregg. She says she took on a role of being strong and invincible but her voice cracks as she remembers how the taunting hurt her. "I had such a tender heart," she says. Jacobus says her parents' big mistake was that they didn't ask her how kids were treating her, and she didn't know how to bring these things up on her own. She begs adoptive parents to talk with their kids about these things. "Ask them!" she pleads. When Jacobus was adopted in 1956, adoption experts were skeptical that foreign adoptees would ever fit in. The answer was to Americanize them - effectively, to raise them as if they were white. By the time Park Gregg was adopted in the 1970s, parents like hers took a "love is blind" approach to race and color; they believed racial differences should be ignored because they didn't matter. Both attempts failed to prepare kids for a society that would never accept them just as Americans, a society that was not color-blind. |

||

|